On Friendship

Commentary column of the Guardian Review (2005)

Friendship is a little like the practice of biography. We can't choose our families, but we can our friends and subjects. In a sense the biographer chooses a companion in the past, and lives on close terms with this person for a number of years. It can be closer, in its way, than relations with the living. This was so in the most intense and melancholic way for Tennyson who clung to the dead Arthur Hallam, while memorialising the formative impact of this friend: "I felt and feel, though left alone,/ His being working in my own, / The footsteps of his life in mine."

My Cape Town friend Elizabeth Gevers, who has a keen eye for a lapse in friendship, detects my absence of attention when I think it disguised. This tends to happen in mixed company when some man is holding forth with dogged confidence. After a recent lunch party, I accepted an offer of a lift, but gratitude faded as the driver talked all the way about cars and their "emissions". Once, at an Oxford High Table, before most colleges went mixed, I deplored the old custom of caning in public schools. The dons, all of them men, stopped eating and there was an awkward silence. At length, a kind old classicist whom I particularly liked, said, "Six juicy ones did no one any harm." His colleagues nodded sagely. Most of them had to be talked to about themselves. Such oblivion would be astonishing were it not so common. Is it habit? Or can it be atrophy of imagination, not the rarefied imagination but our normal endowment, what George Eliot called "sympathy" – the secret of characterisation, she said, lies in deep human sympathy. For George Eliot, there was no artificial gap between the imagination of the novelist intent on character, and that of an ordinary social being. Her novels show imaginative sympathy to be a trait anyone – even the miserly recluse Silas Marner - can learn to cultivate.

Though mixed parties are often tedious, they have the advantage of enhancing, by way of contrast, the stimulus of chosen friends – including biographical companions from the past. The longer I lived with Charlotte Brontë and Mary Wollstonecraft, the more I admired their flair for friendship – their efforts to see, hear, and draw out others (Brontë, the discerning Scottish acumen in her light-hearted publisher George Smith; Wollstonecraft, the domestic affections lurking in the frosty philosopher Godwin who didn't care for women's rights).

Unlike friendship, biography can be a one-sided affair. It can happen that the companion from the past does not welcome the relationship, as Henry James imagines in his tale "The Real, Right Thing" where the dead subject - who had been, in fact, a friend - bars his biographer's way. Yet, for the most part, friendship and biography can converge to advantage, as when Virginia Woolf invites insight from Vita Sackville-West: "What I am, I want you to tell me." Then she dares a step further: "if you make me up, I'll make you."

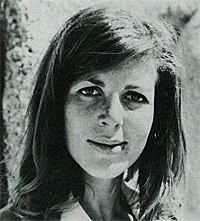

If we could "tell" who we are, or if a friend could "make us up", we would, in a way, create one another. When I recalled three school-friends who died young (Shared Lives), it was like peering into a provincial backwater, which Cape Town was in the fifties : a backwater polluted not only by the rising tide of apartheid but also by stagnant channels of womanhood. The contorted engineering of apartheid was so blatant that it alerted us to the crudity of identities based on race and gender, and to the warping plots that would ensue. At school, our revulsion for the biographic narratives that seemed to lie ahead, encouraged friendship as a liberating alternative. Together, we dreamt of emigration and other transforming plots of existence. A flair for friendship as a form of creativity – beyond anything I have since encountered – was the gift of one girl with cropped red hair called Flora Gevint whom I met on the first day of high school.

The daughter of Jewish refugees whom she protected and also alarmed (finding they had given birth to an explosive alien), she bounced up, at eleven, amongst cowed girls and demanded to know who we were. Perched on her desk, she asked this of twenty-five girls in succession. There was something in her manner so innocently curious that she didn't invite ridicule. Her demand to know was intrusive but exciting. She invented her friends, made us up, conferred on us qualities that were congenial to her. The more unpromising we were, the more resourceful she became – she liked the hopeless ones best. Since I was plain and freckled, she gave me, at sixteen, a charge of confidence. Since Phillippa, was blighted by her sister's death, she infused a continued surge of life; and later, when Ellie, a clinical psychologist, grew lonely and drank, despairing of a succession of partners who sapped her strength, Flora restored her to clarity. All of us she urged to play our parts in character.

Refusing to yield to a predictable future, she broke off her wedding at its rehearsal. Unwilling to violate her integrity, she lived from crisis to crisis. A more formless life is hard to imagine. And yet, as I remember the passion with which Flora urged her friends to be and do, I wonder if there are forms of action like friendship which leave no record but are as creative in their way as more public forms of creativity. In her novels of provincial life, George Eliot could shape her sympathies with moral acumen. But, articulate as Flora was, and fearless in her truth to experience, she could not transmute life into art. Her skill was to shape people, not works; and this, I now see, was the pattern of her life – possibly, the pattern of many unwritten lives that are attuned to what Middlemarch calls "the roar from the other side of silence".